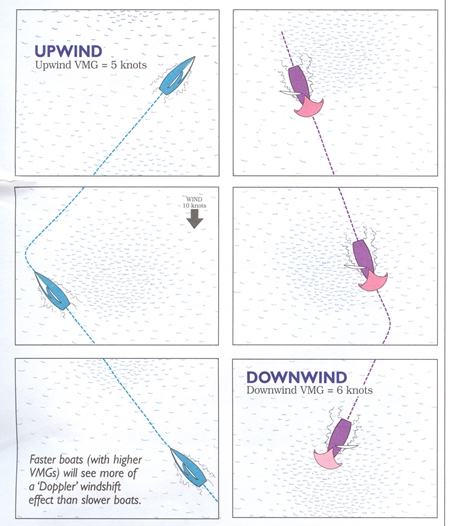

Changing Gears. In sailboat racing, change is continuous, you have puffs, lulls, lifts, headers, bad air, waves, tacks and so on.

It’s rare that you can set the boat up and sail for too long without changing something. To go fast you must constantly adjust the trim of your boat and sails. We actually use many different settings to cover the full range of conditions in which we sail. To change from one gear to another, we usually have to make multiple adjustments.

As an example, when you sail into a lull, you typically ease your mainsheet and bear off slightly. When the wind increases, you trim in and head up.

When you get a lull you don’t put a softer batten in the top pocket or change your mast rake. You might do these things when you set up on the beach but they aren’t normally considered when changing gears.

Keep Your Head Out Of The Boat

A mistake I see out on the course more often than I should is heads in the boat changing major settings. Few changes you make on a beat will make enough extra distance to compensate for the loss made whilst making the adjustment.

It is worth noting that in a race of 60 minutes, with 4 upwind legs you will only be on each upwind for about 8 -10 minutes.

An exception to this is of course if there has been a major change in the weather.

In sailing it’s relatively easy to set your boat up so it will go fast in one particular condition. When the wind and waves remain constant, it’s easy to zero in on the sail shape and other variables.

The problem is that conditions almost never stay constant.

You may get your boat going fast in one condition, but if you don’t adjust things when conditions change, you will not be going as fast as possible, that’s why the ability to change gears is so important for boat speed.

The best sailors might be in the right gear for 90% of a race. The sailors at the other end of the fleet might be in the right gear only 50% of the time or less.

Clues for when to change gears –

- Trust your sense of feel. Indicators like helm pressure or angle of heel will tell you whether the boat needs more or less power

- If your performance relative to the nearby competition is not great, there’s a good chance you are in the wrong gear.

-

Look for visual clues. Many changes that require a gear change are things you can see before they reach you (e.g. puffs, lulls, waves). Keep your eyes open.

Most racing sailors are good at “shifting up” when they get an increase in wind pressure. Puffs are generally easy to see and their effect on your boat is easy to feel.

The ability to change down is a different story, and this is where the best sailors make their biggest gains. It’s harder to detect decreases in the wind, so most sailors don’t downshift soon enough or far enough. The result is they compound the negative effects of sailing into a lull.

If you want to get better at changing gears and going faster for a greater percentage of the race, work hard on shifting down.

Try to shift sooner, more quickly and further when you encounter lulls, bad air, waves or any other situation where you might slow down.